Every teacher has experienced it. You watch a student engage in some unconscionable behavior, and you ask yourself, “Why?”

Why would a student chew on her own shoe? Why would a student chase the classmate he likes so incessantly that he brings her to tears? Why would a student who is lonely lash out at classmates who offer friendship?

Applied behavior analysis (ABA) helps to answer these questions. According to ABA, every behavior serves one of four functions. In identifying these functions, ABA also provides a pathway toward more effective behavior.

Read on to learn more about ABA and the four functions of behavior.

What Is Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA)?

ABA breaks every behavior down into three parts. These include the antecedent, the behavior, and the consequences. The antecedent is the stimulus that causes the behavior. The consequences, in turn, can reinforce the behavior or promote change.

ABA therapy studies and manipulates these three components to promote pro-social communication and behavior skills. According to ABA, all behaviors are learned, and all behaviors have a goal. At any given moment, a person engages in the behavior she believes will best accomplish her goals. Modifying behavior involves changing these calculations by changing the stimuli and consequences.

What Are the Four Functions of Behavior?

For an ABA therapist, asking “why” a student does what he does is neither an idle question nor an expression of frustration. Rather, it is an academic and professional query.

According to ABA, every behavior—even those most difficult to understand—has a purpose. Effective ABA therapy requires understanding the purpose of misbehavior from a student’s perspective. It then requires teaching the student more effective ways to achieve that purpose.

ABA identifies four functions for behavior:

- Attention

- Escape

- Access to tangibles

- Sensory stimulation

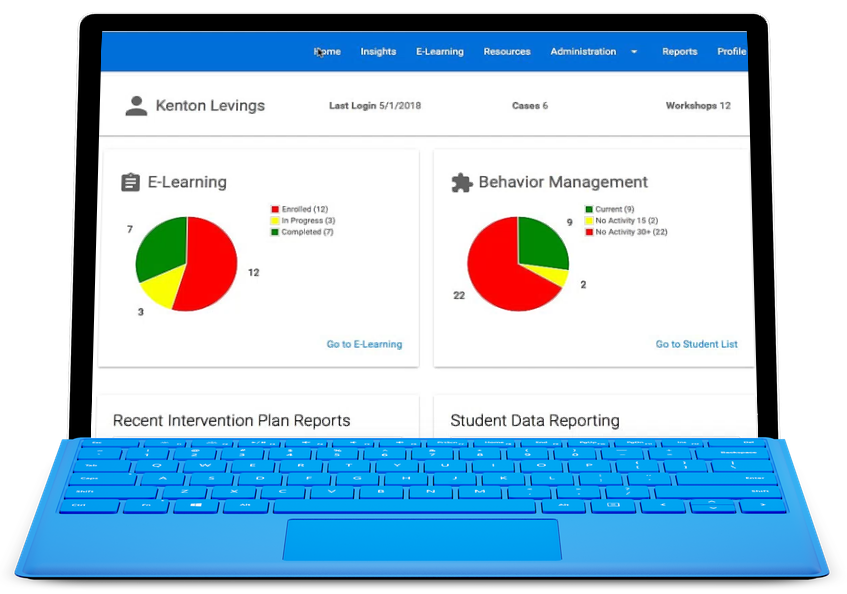

Understanding the purpose of a student’s behavior requires significant monitoring and record-keeping. Modifying negative behaviors, in turn, requires targeted strategies and individualized plans.

Attention

Receiving attention from others is a basic human need. When a child’s needs for attention are unmet, she may engage in behaviors that teachers, classmates, parents, and therapists consider undesirable.

Often, these undesirable behaviors entail negative consequences, including formal punishments and the natural responses of other parties. In both cases, these negative consequences figure into a student’s decision to continue or repeat the behavior.

At the same time, though, imposing consequences requires teachers and classmates to direct attention to the offending student. If the misbehaving student’s goal was attention, he learns, despite any other consequences, to associate the misbehavior with the achievement of that goal.

Consider the following example:

Desperate for attention, a student calls out and interrupts a classmate. The classmate gives the interrupting student a dirty look. The teacher, meanwhile, imposes a formal consequence. Perhaps the student must flip a card or put a check next to his name on a behavior chart.

In both cases, however, classroom instruction is put on hold. All eyes are on the misbehaving student. From the misbehaving student’s perspective, this “mission” is “accomplished.”

An effective ABA response to this situation requires acknowledging the offending student’s unmet needs. It then requires teaching the student more effective ways to gain positive attention. Ignoring attention-seeking behaviors and using positive reinforcement for pro-social behaviors are common strategies.

Escape

The second function of the behavior is an escape. A student seeking escape wants to avoid a situation, experience, or task. Often, students try to escape tasks they find frustrating. They likewise may avoid situations where they feel uncomfortable. As with attention, a student’s desire for escape may be so strong that they discount other negative consequences they may experience.

Take the following example:

A student is embarrassed at having to stand alone at recess. She knows that students who misbehave sometimes lose recess privileges. Thus, she chooses to misbehave. Maybe she talks back to the teacher or lashes out at another student.

In the process, she might develop a reputation for being unkind. She may even realize that, in the long term, this reputation makes it more difficult to form friendships. However, she receives immediate gratification in the form of lost recess privileges. Regardless of any other consequences, she succeeded in her goal of escaping an uncomfortable situation.

An additional example shows how escape-seeking behaviors can mask underlying academic difficulties.

Consider the following:

A student struggles with writing. He “knows” he won’t get a good grade on his essay. He also knows that even trying to write that essay will leave him feeling overwhelmed. So he chooses to put his head down when he should be writing.

Perhaps his teacher responds by deducting participation points. She might even write him up. If she does not also address the underlying cause of the student’s behavior, however, an opportunity for academic and social-emotional growth is lost.

A more effective response to this situation might involve working with the student to break an overwhelming assignment down into manageable chunks. It might also involve providing scaffolds, such as outlines or sentence starters.

Access to Tangibles and Activities

While some behaviors seek escape, others pursue resources and experiences.

Take the example of a student who has a question or doesn’t understand how to complete a task. Maybe the student considered asking the teacher, but the teacher is busy. If the student hasn’t learned patience and self-discipline, waiting her turn may not even cross her mind.

Instead, the student may disregard a teacher’s instructions to work independently on this task and ask a nearby classmate for help. Despite any ensuing consequences, the student achieves the intended aim. She gets an immediate answer to her question.

Another common example of a student seeking access occurs when a student rushes through his work so that he can enjoy free time.

Addressing these and other situations involves teaching students to regulate their own behavior. Patience, goal-setting, and long-term planning are skills that can and must be taught. Social-emotional learning (SEL) helps students develop these competencies. Combined with positive reinforcement, SEL instruction can promote positive behavioral change.

Sensory Stimulation

Finally, a student’s behavior can fulfill her need for sensory stimulation.

Students with autism can struggle to respond appropriately to sensory stimuli. They also often exhibit repetitive behaviors. These repetitive behaviors vary. Rocking and tapping a pencil are common examples. In all cases, these behaviors provide sensory stimulation that the student finds calming.

Autistic students are not the only ones who seek sensory stimulation. In fact, everyone finds pleasure in certain sensory stimuli. Often, students engage in activities that provide this pleasure without thinking about the consequences.

When these automatic behaviors become distracting, ABA therapy can help. A student who becomes aware of repetitive behaviors—and the sensory needs those behaviors meet—can find more effective and less disruptive outlets.

ABA: Identifying Students’ Needs and Finding More Effective Ways to Meet Them

If you’re a teacher who has asked “why” your students behave as they do, you are in good company. You’re also on the right track. Informed by this article, take an open-minded approach to answer that question.

If you’re a school counselor, psychologist, or behavior interventionist, you can support teachers’ efforts to manage student behavior. Learn how in our free monthly webinar series.

Finally, if you’re the director of special education, find out how Insights to Behavior software, which is based on ABA best practices, can create legally-defensible behavior plans in under an hour. Schedule a 30-minute online demo today.